The CLIMB Study

Breast cancer remains a significant health concern for older women, who account for appoximately 50% of those diagnosed with the condition. Older patients often have reduced physiological reserve and clinically significant comorbidities, and are more susceptible to both undertreatment and to overtreatment, as well as being more likely to experience treatment toxicity and early discontinuation of therapy.

Around 70-80% of breast cancers are categorized as estrogen-receptor (ER) positive. Regardless of the disease stage or setting, a majority of patients diagnosed with ER+ cancers are likely, at some point during their treatment course, to be treated with endocrine therapy (ET), which works to block or prevent estrogen signaling, and is typically taken for between five to ten years in the adjuvant setting. In general, ET comes in one of two forms, either aromatase inhibitors (AI), such as exemestane and letrozole, or selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) such as tamoxifen.

Endocrine therapy (ET) has well-established roles and a strong evidence base in both palliative and adjuvant settings, including among older women specifically. However, anecdotal concerns regarding treatment-related cognitive decline may lead to hesitancy among some oncologists in prescribing these therapies, resulting in a possible undertreatment of this population. In this regard, there is a clear need for robust evidence to establish whether these toxicities exist, and to what degree, if any, they affect patients.

In this blog post, we present an in-depth interview with Dr Joosje Baltussen, a geriatric oncology researcher based at the Department of Medical Oncology, Leiden University Medical Center, and first author of a recent paper from the CLIMB study (European Journal of Cancer, May 2023).

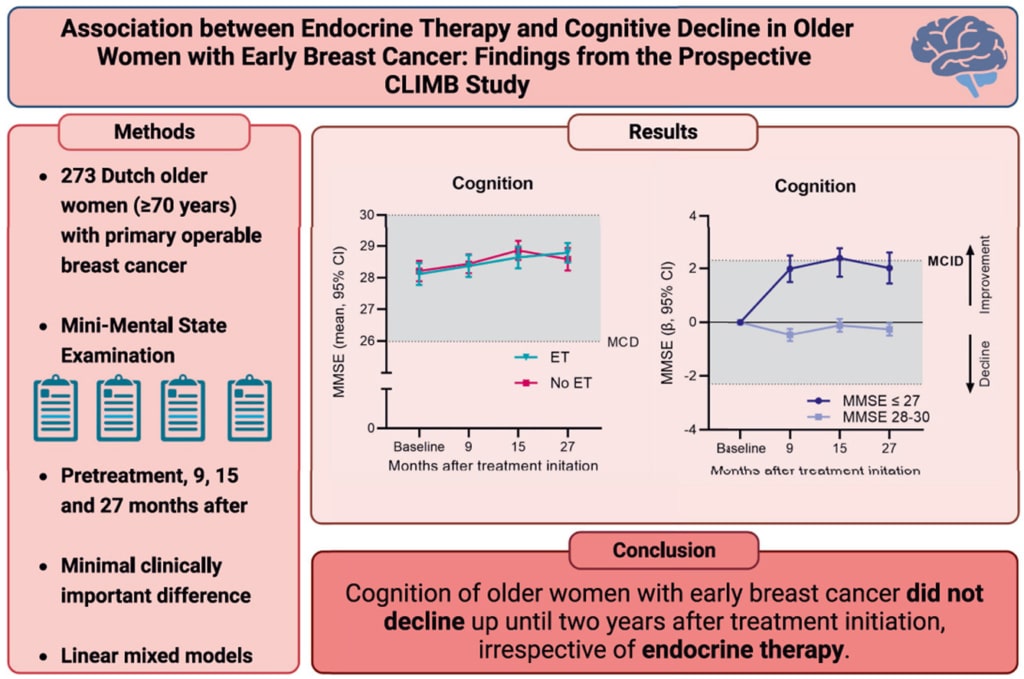

CLIMB is a longitudinal cohort study that investigated patient-reported outcomes, such as cognitive functioning, in older women (aged ≥70 years) with early breast cancer during the first two years following treatment initiation. One of the aims of the CLIMB was to assess cognitive functioning during endocrine therapy and to identify subgroups that might be susceptible to accelerated cognitive decline.

The key finding of this study was that cognitive functioning did not decline to clinically meaningful differences in women receiving ET; in fact, the subgroup of women with impaired cognition at baseline exhibited clinically meaningful improvements in cognitive function. The results of the CLIMB study suggest that concerns about cognitive decline should not be a reason to withhold ET in older women with breast cancer, even for those with low educational status, high age, or impaired mobility.

INTERVIEW

- What inspired your team to investigate cognitive function in older women with breast cancer?

Our team wanted to investigate cognitive functioning in older women with endocrine therapy due to the observation in clinical practice that some older and frail women seemed to experience a rapid cognitive decline during endocrine therapy. Our team hypothesized that this might be the subgroup of women with an impaired cognition at treatment initiation.

- What was the main hypothesis of your study, and how did the results align with or contradict it?

The main hypothesis of the study was that cognitive functioning would not decline in the whole population receiving endocrine therapy, but that there are subgroups susceptible to accelerated cognitive decline. The results of the study partly supported this hypothesis, as the majority of women did not experience cognitive decline, but we were surprised to find that the subgroup with impaired baseline cognition did not experience an accelerated decline and even showed a clinically relevant improvement of cognition.

- How do your findings compare to previous studies that have investigated cognitive function in breast cancer patients?

Previous studies have yielded conflicting results regarding the cognitive functioning of older patients treated with endocrine therapy. A large prospective study by Mandelblatt also found an intact cognition 12 and 24 months after endocrine treatment, similar to healthy controls. In another study by Mandelblatt, the majority of older breast cancer survivors maintained good long-term self-reported cognitive function, and only a small subset who were exposed to chemotherapy manifested accelerated cognitive decline (a finding that was not confirmed in our study). Some studies did report a declined cognition, especially on verbal memory and executive functioning scores, but these studies mainly included younger and more fitter patients than the average older population seen in daily practice.

- In your study, you found that even women with cognitive impairments at baseline exhibited clinically meaningful improvements in MMSE scores. Can you discuss some possible explanations for this improvement?

Possible explanations for the clinically meaningful improvements in MMSE scores seen in women with cognitive impairments at baseline include the phenomenon of regression to the mean (extreme outcomes are often followed by more moderate ones), the initial shock of receiving a cancer diagnosis causing an impaired cognition during treatment initiation and practice effects on the MMSE

- How do your results contribute to the ongoing debate regarding overtreatment and undertreatment of older women with breast cancer?

Our findings contribute to reducing undertreatment, as our results suggest that concerns about declining cognition do not justify withholding endocrine therapy in older women. Nevertheless, although risk of cognitive decline may be low, in some cases, other potential harms of treatment may still outweigh the benefits, particularly in patients with a low risk of recurrence and high risk of other-cause mortality.

- Can you share any insights into ongoing or future studies that will build upon your findings and continue to explore cognitive function in older women with breast cancer?

Our team philosophized about performing a small pilot study with older women treated with endocrine therapy in which we will conduct a battery of neuropsychological testing to further investigate cognitive domains. Moreover, measurement of cognitive functioning 5 years after treatment initiation would further clarify the effect of endocrine therapy on cognition, as endocrine therapy is usually prescribed for at least five years.

- What are the most important takeaways from your study for healthcare professionals, patients, and their families?

The most important takeaway is, in my opinion, that worries about early cognitive decline among clinicians and patients and their families should generally not be a reason to withhold endocrine therapy in older women, not even in those with low educational status, high age or impaired mobility.

References:

Baltussen JC, Derks MGM, Lemij AA, et al. Association between endocrine therapy and cognitive decline in older women with early breast cancer: Findings from the prospective CLIMB study. Eur J Cancer 2023;185:1–10.